Image: Marriage of John Mashford and Mary Cann, Coldridge.

Elizabeth Mashford's father was a tailor and so her life

should have had a modicum of comfort, unless of course she was a 'poor

relation' taken in and more of a Cinderella than a daughter of the house.

Although that remains conjecture, but we still have no

answer as to why she appeared to be less literate than her siblings when the

family was far from being the poorest of the poor.

A UK researcher , Peter Selley, came up with a bit more information, including the

following tidbits referring to John Mashford's apple tree, and his 'seat' in the Church. He also said,

tailors were often highly valued members in a village and taking it further,

one can assume, given their profession,

involved across the social spectrum if their skills were good.

He wrote:

Here is another bit of info from a memorandum which I noted in the Coldridge Church Register which I copied out a couple of months back but it may be relevant.

Here is another bit of info from a memorandum which I noted in the Coldridge Church Register which I copied out a couple of months back but it may be relevant.

Memorandum

The second seat under

the gallery on the north side of this church for women next to the seat that

belongs to Frost (?) belongs to John Mashford for the house adjoining the pound

in the town. Being at his own expense for making it by the liberty of the

minister and church wardens May the 10th 1817.

“Frost” is probably

correct being a farm in Coldridge and I think that having a pew in those days

was a perk of land owners who paid

tythes to the parish.

Just before I hit the

send button i thought I ought to check out the apprentice registers on Ancestry

and there is this entry:

Sept 18 1757 John

Mashford of Coleridge sergemaker – Fran(ci)s Canne (Coleridge transcribed as Cotheridge).

Francis Canne being his apprentice.

NB: This brings in the connection for Elizabeth's mother,

Mary Cann Mashford.

Image: Elizabeth Mashford, baptism, Coldridge.

I would imagine that

this would be JM the tailor’s grandfather. That this chap had an apprentice

shows some social standing.

This may interest you – some of the glass is early 16th

century

http://www.cvma.ac.uk/jsp/location.do?locationKey=353&mode=COUNTY&sortField=COUNTY&sortDirection=DESC&rowsPerPage=20

A Remarkable Fact”

“On an apple tree

belonging to Mr John Mashford Coldridge might be seen last week ripe fruit and

full blow blossom”

The Western Times

(Exeter, England), Saturday, October 11, 1834; pg. 3; Issue 354. British

Newspapers, Part III: 1780-1950.

I found the following on another website regarding the 'life

of a tailor, in Devon, at the same time John Mashford was plying his trade.

By 1881, William

Hornsey Gamlen was a substantial figure in Devon. He was a Magistrate who had

passed a lifetime as a farmer in Devon.

He was a member of the

Devonshire Association and in 1880, gave an address to the members describing

life on a mid-Devon farm in the 1820s . His style of writing is simple and

direct and his listeners must have known that they were sharing the personal

experiences of his youth as he took them back to the time when he was a

teenager:

"The farm boys usually wore a fustian* jacket and waistcoat,

leather breeches and shoes; boots were never worn; pieces of bag were tied

round the ankles as a sort of gaiter and called "kitty bats" to keep

the earth out of the shoes. These shoes, made of hide leather, were washed

every Saturday night, and well-greased after being dried, and in time became

almost as stiff and hard as wood.

The village tailor used to go to the farmhouses, and make and mend the

boys' clothes with materials kept for the purpose, and received eight pence and

sometimes a shilling a day and his food for doing this. He sat on the kitchen

table at his work, and kept the mistress employed in supplying his requirements

of more cloth, thread, buttons etc. till her patience was well worn. On one

occasion, in hot weather, an apprentice girl whispered "Missus, missus,

the tailor is asleep!" and received for answer: "Hush! for patience'

sake don't wake him; I've had plague enough with him already."

In some places, the shoemaker too went to the houses and mended what

required repair from a stock of leather kept for him."

In earlier time, tailors visited their clients in their own homes so

the terrible conditions under which the actual work was carried out were seldom

revealed. In this picture, we see an entire family huddled as close to the

window as they can get, struggling to complete military uniforms for delivery

in less than 24 hours.

Ready-made clothing is so easy to obtain today that we have forgotten

how our ancestors coped with the problem of obtaining decent clothing. Old

wills frequently show bequests of clothing.

Until the end of the 19th century, working women would have made their

own garments or, for special occasions, enlisted the help of the village

dressmaker who also made stays and bonnets. Fabric was used and re-used and

skilfully repaired if damaged, before being cut down to make children's

clothing. Even so, women did visit men's tailors because they provided an

essential service - they had the facility to bleach out colour and to dye

garments black - absolutely essential following a death in the family.

Men's shirts were made at home. These were long garments, the back

tails being drawn up between the legs as an alternative to modern underpants

during the day. At night, the front and back tails were let down and the same

garment was used as a night shirt. The village tailor provided suits for

weddings (which a man would continue to use on Sundays for years after),

working trousers and waistcoats. Stockings for all the family were knitted at

home and boots, shoes or clogs came from the village shoemaker.

The 1851 census gives a figure of 599 for the population of the village

of Atherington and its environs. No less than 5 tailors served the needs of

this comparatively small population - Robert Gibbs, George Loosemore and

Richard Slee all had tailoring businesses of their own, providing competition

for George Stedeford, who in the absence of a son of his own, took his grandson

Thomas Beer into partnership in his declining years. Two dressmakers - Mary Ann

Govier and Sally Loosemore were on hand to cut down adult clothing for children

or to provide finery or mourning clothes for the women of the village.

http://www.devonheritage.org/stentiford/Issue_29/Article1/4May1art3.htm

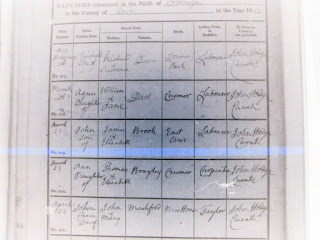

Below, birth/baptism records for Elizabeth's siblings.