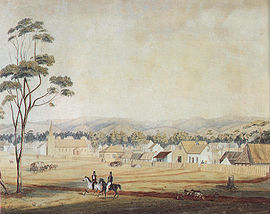

Image: Destitute Asylum, Adelaide.

Fellow researcher, Luke, has gathered some more information on Elizabeth Mashford Lewis Atkins, which show that she was a woman of property, following the deaths of her brother, George May Mashford and her mother, Mary Cann Mashford, in 1850, barely eight weeks apart.

She may also have married Edward Atkins without proof that her first husband, Peter Lewis was dead, and in fact, knowing he probably was still alive. Alternatively she was a little dim although there does not seem much evidence for that explanation.

And according to the notice published in 1865, within three years of the death of her much loved brother and mother, Elizabeth and her children were left destitute in Melbourne after being abandoned by Peter Lewis. Although, if Elizabeth had inherited money from her mother, since her brother's Will was not finalised until 1856, she must have had enough money to get back to South Australia with her sons.

George Lewis was born, July 8, 1848 in Kensington and so in 1865, when the notice regarding his father was published, was seventeen, and while underage in law, was not so young. Perhaps Elizabeth feared that if Peter Lewis was alive, she would be revealed as a bigamist.

But that doesn't work, given that she put the notice in the newspaper warning about contact being made with her son. Another possibility is that the notice revealed to Edward Atkins that his wife was probably a bigamist and if he had 'found' or always had religion, that marked the beginning of the end of their relationship. Although Elizabeth did not move to Gladstone until around 1878, some thirteen years away, at a time when her youngest daughter, Mary Atkins, later to be Ross, was pregnant with an illegitimate child. The theory is a little thin to say the least, but conjecture is the way of ancestry research.

John Mashford Lewis, born at Marryatville December 10, 1850, a few months after Elizabeth lost her mother and brother, was Fifteen in 1865. Henry Lewis, born January 22, 1854 died in 1855, in Adelaide.

Elizabeth made an application in Adelaide to the Destitute Board for relief, in 1853, and so it seems that when Peter Lewis deserted her, she was pregnant with her third son, and could not work. Even if she had inherited money from her mother, it may have been very little and not enough to live on while she was pregnant, and supporting a five and three-year-old.

Or indeed, if there was a legitimacy issue, she may have inherited nothing from her mother, or had been prevented by her sisters and surviving brother from claiming it, and was in dire straits until her oldest brother's Will was finalised in 1856.

Whether or not she and her sons lived in the Destitute Asylum, we do not know. Although little Henry's death may well have been the result of living in the poor conditions, away from his mother, which such places demanded. After such a loss, it would be even less surprising that Elizabeth would do whatever she had to do, perhaps marry the first man who asked, knowing that her husband might still be alive, in order to provide a better life for her children.

The history of this institution has been written by Mary Geyer, Behind The Wall - The Women of the Destitute Asylum

Adelaide, 1852-1918

Image: Children of the Destitute Asylum.

It provides an insight into Adelaide's Destitute Asylum and the women who experienced

life behind its walls. Until its

closure in 1917 politicians and governments, Commissions and Boards of Inquiry

tried to solve the problem and cost of destitution to the colony.

South Australia was a free colony, without convicts, planned according to the Wakefield

principles, where there would be no poor or destitute. According to this theory

emigration of the correct proportion of capital and labour would create an

ideal society free from social, economic, political or religious problems. It

would be a self-sustaining society, prosperous and virtuous without the need to

provide for paupers.

As the saying goes, the best laid plans of mice and men. The reality was very different. Almost from the start the South Australian

Immigration Agent had to provide assistance to those in need. In 1843, barely seven years after the colony was established, the government passed its first legislation to deal with poverty. It now became

law that relatives were responsible for the maintenance and relief of deserted

wives and children.

And of course, Elizabeth Mashford Lewis had no relatives in Adelaide who could help her and possibly none interstate or overseas who would or could, and not only was she deserted but pregnant with two small children to feed. With George May Mashford's Will still not finalised one presumes she could not live in his house and with no other relatives in South Australia, is most likely to have been forced to live in the Asylum. Although researcher, Luke, seems to think that she could have lived in her late brother's house. Wherever she lived, times were tough.

During 1849 the Board provided relief to 25 indoor and 114

outdoor destitute. By 1851 this had increased to 63 and 187 respectively. By

1855 it reached an all time high when it had to provide relief to more than

3,000 men women and children, one of whom was our great-great grandmother.

This high number came about as a result of excess

female immigration which resulted in lower wages being paid, a very poor

harvest causing increased unemployment and the large number of wives who had

been deserted by their husbands leaving for the Victorian goldfields. Deserting

husbands were the chief cause of female poverty and it was suggested that these

men should be flogged.

And perhaps it was to the goldfields that Peter Lewis went. Wherever he was, Elizabeth was alone.

If she was in the Asylum it was hardly a pleasant place. It was, like the Poorhouses of England, a place of last resort and nowhere that anyone would live by choice. Men and women were segregated by a

stone wall of nearly three metres. Once admitted, inmates were only allowed to

leave for five or six hours once a week, although pregnant and towing a toddler and a small child, if indeed she was allowed to take them out, dressed in the Asylum uniform, one presumes Elizabeth did not take up the offer of 'time-out.'.

Each day the bell would ring five times, the fist in the

morning to get out of bed, three times a day for meals and finally for lights

out. Asylum women were expected to earn their keep and

were involved in washing for outside customers, ironing as well as sewing

hessian sacks, garment making or embroidery.

Orphans and children of destitute families were admitted but

separated. Parents could visit them once a month but only for two hours. After

1867 this practice was ended when children were sent to industrial schools or

boarded out to families. If Elizabeth spent time in the Asylum, she would have been separated from her small sons.

There was little compassion for destitute pregnant women although Elizabeth did have a record of her marriage and as one of the many abandoned wives due to goldfields fever, may have had an easier time.

Elizabeth had experienced a traumatic few years, but, was resilient enough, it seems to survive and carry on. Her brother, George's Will would be finalised the following year, and within two years of losing her baby son, she would marry Edward Atkins.

For a woman, abandoned by her husband when pregnant, destitute with small children to care for, marrying Edward Atkins, even with his brood of motherless children, may have seemed an offer too good to refuse.

She was tough, but then one had to be in the 19th century, or, as my mother often said: 'It's a great life if you don't weaken, once you weaken you'r gone.' And 'gone' in those days was literally into the gutter.

And perhaps it was because she had been abandoned by her first husband that she chose not to fully trust the second and kept knowledge of her property and wealth a secret from him - just in case. As it happened, for reasons we do not know, that second marriage also ended in separation, although, from the look of it, this time Elizabeth did the leaving when she moved from Wirrabarra Forest to Gladstone in 1872, which is when the records show her purchasing land.

Whatever the reasons for the 'ending' of her second marriage, it seems clear that Elizabeth was resolute in regards to caring for her children, no matter what, and that is a heritage which stood her in good stead and no doubt does for her descendants.

Image: Burnside/Marryatville, Council chambers, 1865.

As Luke writes:

Furthermore, about the house and where Elizabeth Lewis got the money from. I believe the following. Elizabeth Lewis got a quarter share of her brother’s house and something from Mary Cann Mashford’s share. She was married to Peter Lewis at the time and women in the early 1800s could not get a loan from the Banks unless they had their husband’s permission. Peter Lewis may have thought it was in his best interest to give his permission for her to get a loan. Whether the loan was under both names or just her name we will never know. However, they had a mortgage just like any other couple did and had to work to pay it off like any other couple in the early 1800s. As a result, Peter Lewis would have known all about the house as he was still married to her. Also after Elizabeth Lewis paid out her two sisters they took off to Melbourne for good.

If Peter Lewis was still alive, all he had to do was to go to the Norwood and Kensington Council and make some enquiries as to who the owner was and found out where Elizabeth Atkins was living.

It is interesting that Elizabeth Atkins does not seem to have changed her surname with the Norwood and Kensington Council until after she had left Edward Atkins. As a result, if Peter Lewis was still alive, Elizabeth Lewis made it easy for him to track her down to Charlton.

Of course, there was no Post Office at Charlton. I do not know where the nearest Post Office would have been located, more than likely at Melrose, about 15kms away.

What Edward Atkins knew about the whole situation remains unknown. However, if there were any problems in the marriage this notice would have added to it and how Elizabeth Atkins explained everything to Edward Atkins remains unknown.

In addition, it may explain how she got the blocks of Land at Gladstone. She would have had a tenant in the house, thus paying off her loan and even though it was against Bank policy to give a loan to women in the 1800's they may have turned a blind eye because she used the house as security against any loan. I also think she gave a block to George and John Lewis because there was an agreement. They would build her a house on her block for free, in return, they each would get a block.

This is the notice.I found it on TROVE. The notice really does have many ramifications because Peter Lewis could have been very much alive when Elizabeth Mashford married Edward Atkins. For somebody to write to George Lewis they had to have known the address where the Atkins family lived in 1865, how did somebody find out they were living at Charlton?"

“If Peter Lewis, who left his Wife and Children Destitute in Melbourne 12 years since, is still living, this is to caution him or any other person against sending or bringing private letters or messages to my son George Lewis, he being under age. Elizabeth Atkins (formerly Lewis), Charlton Mines, February.”

In addition, Luke has been researching the position of women in regard to taking out loans in the 19th century:

Dear Ms Allen I was wondering if you could help me with a number of questions concerning the status of married women in 19th century South Australia. I have tried to find the answers myself, but to no avail, but then I came across this website during my research.

I am researching my Great Great Grand Parents Edward Atkins and Elizabeth Mashford. Both people separated, but there was no divorce. In November 1872, Elizabeth Atkins purchased five blocks of land at Gladstone SA. On 30 August 1873, Edward Atkins placed a notice in the newspapers stating he would not be responsible for his wife’s debts. I understand that under the SA Married Women’s Property Act 1883/1884 women in SA could for the first time hold, and dispose of any real or personal property. Before this Act, a married women’s property legally belong to the husband. I also understand that married women could not enter into a legal contract without her husband’s approval. However, would I be right in saying that before 1883/1884 the husband could be responsible for his wife’s debt? Would this be the reason as to why Edward Atkins placed the notice in the newspaper? Would such a notice back in the 1800s give Edward Atkins any legal protection if his wife could not pay her debts?

Secondly, I am having real problems in finding out any information regarding the status of women and banking in South Australia in the 1800s. I am under the impression that women could not enter into a legal contract without her husband approval before 1883/1884. Am I right in my thinking? If so, how did Elizabeth Atkins a married, but separated, women buy land under her own name? because she would have to enter into a contract unless she lied. Do not be worried if you have to tell me my GGGmother was a liar because it would not surprise me. She may have married Edward Atkins while her first husband was still alive and I believe that caused the separation.

Furthermore, If she did not have the cash she would have to borrow the money from a Bank. I am under the impression because there were no anti-discrimination laws that Banks could deny married women from opening up their own accounts in the 1800s. Would my thinking be right in this regards? I am also under the impression she would have to lie to the Banks to secure any loan.

Want is interesting about the certificate of title I have in regards to the land is in 1886 she transferred a block of land to her son George Lewis and I have copies of the Gladstone council assessment rates which show her other son, John Mashford Lewis , is paying council rates for another block of land which she owned. As a result, could it be possible that she never took out a Bank loan, but instead, her two sons took out the loan and as repayment, Elizabeth Atkins transferred some of the blocks of the land?

Any suggestion you have would be most helpful. I do have a copy of Helen Jones’ book “In her own name,” and Henry Finlay book about divorce in Australia 1858-1975. However, these books do not seem to cover in any details the information I am seeking. Are you able to recommend a good book on the history of women’s right in South Australia ,or a journal article, which covers the information I am seeking.

Hi Luke,

You've been doing a lot of research there! I'm not sure about legal protection from the newspaper notice, you may need to consult a lawyer on that one, but since before the married women's property act a woman's property went to her husband it is reasonable to assume debt would as well. Your theories about the involvement of Elizabeth's sons also sounds reasonable, but without records of her bank loans and debts it's impossible to say for sure. You can search for further information on the land and title records here:

https://www.sailis.sa.gov.au/home/auth/login You may also find information at State Records if you haven't already tried there:

https://www.archives.sa.gov.au/content/family-history

Re. further books you might try: Elford, K, ‘Marriage and divorce’ in Eric Richards ed., The Flinders History of South Australia: Social history (Adelaide: Wakefield Press, 1986). Margaret Allen contributed this piece to the website but can be contacted directly at the University of Adelaide, where you will find a list of her published works. These may be of use for your further reading also -

http://www.adelaide.edu.au/directory/margaret.allen

You've been doing a lot of research there! I'm not sure about legal protection from the newspaper notice, you may need to consult a lawyer on that one, but since before the married women's property act a woman's property went to her husband it is reasonable to assume debt would as well. Your theories about the involvement of Elizabeth's sons also sounds reasonable, but without records of her bank loans and debts it's impossible to say for sure. You can search for further information on the land and title records here: https://www.sailis.sa.gov.au/home/auth/login You may also find information at State Records if you haven't already tried there: https://www.archives.sa.gov.au/content/family-history