Elizabeth

Mashford Atkins was it seems, nothing if not resilient, and would turn her hand

to anything. By 1885, according to her tax returns, she is working as a

Laundress.

At the age of sixty-six, with her previous occupation as a servant, perhaps taking in laundry is a less onerous way to earn some money. Although, according to the reports of the times, laundering was arduous and required degrees of resilience and strength.

Water had to be hauled to a wood-fired copper, for which no doubt wood had to be split. Large amounts of at least warm water would be required and more for the rinsing. None of which was likely to be coming from a tap in any laundry.

Bedlinen, table-linen, clothes, all had to be washed by hand, on boards, wrung by hand, which never gets out much water, leaving fabric heavier than we would know it, and then hung on a line.

One reason why those who could send out their washing, did, was because it took up so much time, space and effort.

At the age of sixty-six, with her previous occupation as a servant, perhaps taking in laundry is a less onerous way to earn some money. Although, according to the reports of the times, laundering was arduous and required degrees of resilience and strength.

Water had to be hauled to a wood-fired copper, for which no doubt wood had to be split. Large amounts of at least warm water would be required and more for the rinsing. None of which was likely to be coming from a tap in any laundry.

Bedlinen, table-linen, clothes, all had to be washed by hand, on boards, wrung by hand, which never gets out much water, leaving fabric heavier than we would know it, and then hung on a line.

One reason why those who could send out their washing, did, was because it took up so much time, space and effort.

Although

we are used to a weekly wash, these days often daily, by the nineteenth-century it was

considered prestigious to own clothing enough to put off laundering for several

weeks, again because of the effort involved in getting things washed. In a “well-known chronicle

of English rural life” by Flora Thompson it is said of the town postmistress in

the 1890s that she:

kept to the old middle class custom of one

huge washing every six weeks. In her girlhood it would have been thought poor

looking to have had a weekly or fortnightly washday. The better off a family

was, the more changes of linen its members were supposed to possess, and the

less frequent the washday (24).

Back-breaking

was a term often used for laundry work, but it was also something readily done

by anyone, since the skills were widespread and the basic equipment readily acquired.

The laundry mangle had been around since the late 18th century, but

whether they had made their way to rural South Australia by the late 19th

century is the question. Probably they had and Elizabeth did have access to

monies following the deaths of her older brother and her mother, so we can only

hope she had one to use, along with the help perhaps, of her now grown

daughters.

Traditionally older women, widows, or divorcees, or married women short of money, were the ones who took up laundering. Washing was something which could be done from home and which allowed attention to be given to personal needs at least, some of the time.

It was an ongoing, sloppy, messy process, but it allowed a degree of flexibility which working outside the home did not. And it may well have been something which Elizabeth and Mary did together, in order to support themselves and Mary’s illegitimate son, since she was not to marry Charlie Ross until 1888.

Laundry work enabled women to remain at home to care for their children while still earning an income.

Traditionally older women, widows, or divorcees, or married women short of money, were the ones who took up laundering. Washing was something which could be done from home and which allowed attention to be given to personal needs at least, some of the time.

It was an ongoing, sloppy, messy process, but it allowed a degree of flexibility which working outside the home did not. And it may well have been something which Elizabeth and Mary did together, in order to support themselves and Mary’s illegitimate son, since she was not to marry Charlie Ross until 1888.

Laundry work enabled women to remain at home to care for their children while still earning an income.

A

laundress working at home would, in today’s vernacular, be an entrepreneur. As

such, she was typically not the delicate Victorian lady. The Royal Commission

on Labour reported the comment that laundresses were “the most independent people

on the face of the earth.” Running a business required more than knowing how to

iron a lace collar or having a back strong enough for heaving sodden linen

about.

From the photos we have it is clear that Elizabeth was a solid woman and young Mary, a slight little thing. No doubt between them they could handle the demands of laundry work.

This description from Ronald Blythe’s, The View in Winter, of a servant’s life is revealing, although, Elizabeth and Mary at least had the benefits of a more benign Australian climate than British washerwomen had to endure:

From the photos we have it is clear that Elizabeth was a solid woman and young Mary, a slight little thing. No doubt between them they could handle the demands of laundry work.

This description from Ronald Blythe’s, The View in Winter, of a servant’s life is revealing, although, Elizabeth and Mary at least had the benefits of a more benign Australian climate than British washerwomen had to endure:

She used to wash for the big house and all

this linen was brought to her cottage in a wheelbarrow. How she used to manage

all this washing in her cottage without the use of anything, I don’t know. She

had an old brick copper. She said she’d stand up till two in the morning

ironing with a box iron. Sixpence an hour she was paid. He husband was away in

the army and she washed. (34)

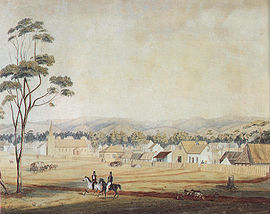

Photo: Adelaide, in 1839.

Fellow researcher, Luke has been continuing to work on Edward/Edwin Atkins:

“The Police Gazette gave a description of Edward Atkins he was from Cirencester, aged c19 years, 5-foot tall and 6 1/2 inches, an oval face, grey eyes, brown hair, and Blacksmith.

This description matches the Gloucestershire Gaol record for Edwin Atkins. From Cirencester, a Blacksmith, aged c19 years, 5 foot tall 6 ½ inches, brown hair, this time he has blue eyes, but in a dark prison room an easy mistake to make. Upon arrival in NSW the Convict Indent record gives the same description of 5 foot 6 1/2 inches tall brown hair, grey eyes, etc. it is all the same person.

Photo: Adelaide, in 1839.

Fellow researcher, Luke has been continuing to work on Edward/Edwin Atkins:

“The Police Gazette gave a description of Edward Atkins he was from Cirencester, aged c19 years, 5-foot tall and 6 1/2 inches, an oval face, grey eyes, brown hair, and Blacksmith.

This description matches the Gloucestershire Gaol record for Edwin Atkins. From Cirencester, a Blacksmith, aged c19 years, 5 foot tall 6 ½ inches, brown hair, this time he has blue eyes, but in a dark prison room an easy mistake to make. Upon arrival in NSW the Convict Indent record gives the same description of 5 foot 6 1/2 inches tall brown hair, grey eyes, etc. it is all the same person.

While

I was in Adelaide, recently, I went to the Supreme Court. I was told, or I read

somewhere, that a person can go to the Supreme Court and they have an index

database of all Supreme Court trials from the 1800’s. I found out where to go

and I had a look at the database.

There

is a civil matrimonial case lodged by Elizabeth Atkins in 1873. This could well

be our Elizabeth Mashford because 1873 is very close to 1872 when she purchased

some land in Gladstone.

If

this is Elizabeth Mashford it may well be against Edward Atkins for some reason

and will let us known why the couple separated. I doubt it is a divorce matter

because their names do not appear in the divorce list from the State Archives

divorce index list from the 1800’s.

However,

to read the court case is not straightforward and may take some time. First of

all I have to write to the Register of the Supreme Court and request permission

to access the court case as all Supreme Court cases from the 1800s are still

restricted.

If

I get permission I then have to go to the State Archives and I can only do this

in the first Thursday of every month. Secondly I have to then show the letter

from the Register to a staff member and then they have to find the particular

court case, which in itself is no mean feat. Sometimes they just bring out a

big box and then you have to go through all the court cases to find the one you

want which can take some time

I

will write a letter to the Register and I will keep you informed about the

outcome.

As

for Edward Atkins there is a newspaper report (Trove) of how he got into a

fight along the Para (Gawler) in 1839. The newspapers said he was allowed bail.

However just because a person is allowed bail that does not mean they can meet

their bail conditions and have to serve their time in Gaol.

I went to the State Archives and due to the very bad sloppy paperwork which people kept it is not clear how long he was in the old Adelaide Gaol. The newspapers say he was released, but it also could mean with time served. He was in the old Adelaide Gaol it is just a matter of how long. It may have been for a good three months or just for a few days before the court case took place.

I went to the State Archives and due to the very bad sloppy paperwork which people kept it is not clear how long he was in the old Adelaide Gaol. The newspapers say he was released, but it also could mean with time served. He was in the old Adelaide Gaol it is just a matter of how long. It may have been for a good three months or just for a few days before the court case took place.

However,

when I say the old Adelaide Gaol I do not mean the one next to the railways

line in Adelaide. In 1839-1840 that Gaol had not been built. The Gaol he was in

no longer exists and it use to be in between Government House and the military

parade grounds on King William Street.”

This would be about two years after Edward Atkins completed his seven year sentence in New South Wales, which gives him plenty of time to make his way to the fledgling new colony of South Australia, established in 1836.

If he headed West for a new start, it was not a very promising one at this point.

The Trove report:

This would be about two years after Edward Atkins completed his seven year sentence in New South Wales, which gives him plenty of time to make his way to the fledgling new colony of South Australia, established in 1836.

If he headed West for a new start, it was not a very promising one at this point.

The Trove report:

Thomas Fielding, Joseph Best, and Edward

Atkins, were charged with assaulting Thomas

Wilson at Mr Reed's station on the Para, on

the

30th of last month. The Clerk of the Peace,

stated that this was so serious a case that

he was

instructed to request his Worship to send

it for

trial at the next general gaol delivery.

The prisoners were accordingly committed, but allowed

The prisoners were accordingly committed, but allowed

to procure bail. The complainants who

presented

a shocking appearance, is an inmate of the

in-

firmary, and a certificate from the

Colonial

Surgeon was handed in stating that he was

suf-

fering from compound fracture of the jaw.